Color lines dim and brilliant characters come to life—a model for inclusivity in professional wrestling where you might least suspect it.

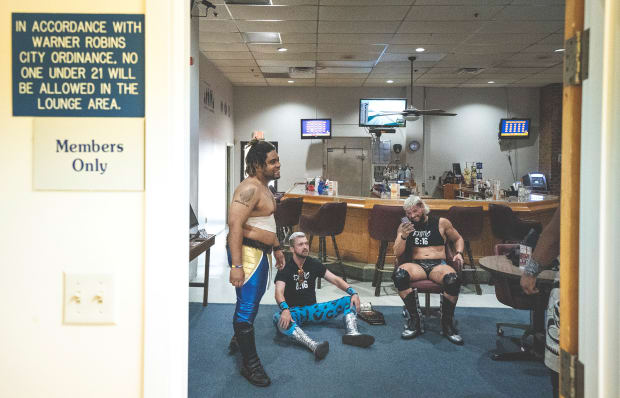

Through the windowless, carpeted taproom; past the Keno lottery machine and the painting of a bald eagle and the bartender in a yellow DON'T TREAD ON ME T-shirt, an unmarked door hangs slightly ajar. Inside, Austin Towers—The Chief, as he’s known in this space—folds his seven-foot frame at the waist to grab a slice of pepperoni from a Little Caesars box beside a picked-over veggie tray and a stack of floral-print paper plates. He settles in next to Brandon Whatley, The Serpent Assassin, who stands with arms crossed, a coiled viper stamped across his purple tights. Seated on a swivel chair, wearing a dark singlet, Eric Silva, The Ghost, twists the cap off a 5-Hour Energy drink; Shawn Angelo Montana stretches green KT Tape across his lats; and Ehren Black gathers his thoughts before stepping toward the center of the room. They’re professional wrestlers, they’re Black, and at 4:30 on a Sunday afternoon they’re huddled in the back of VFW Post 6605 in Warner Robins, Ga., counting down the final adrenaline-filled minutes before a show.

At last, this band of moonlighting sportsmen—a trucker, a chef, three medical transportation drivers—gathers around Black, who has performed in nearly every show since the upstart Georgia Independent Professional Wrestling company began two years ago. “Ladies and gentlemen, welcome to our version of WrestleMania,” he says forcefully, and the locker room chatter halts. “Tonight is the night you put everything on the line. You show your emotion. You show your pride. You show everything.”

He pauses to take in the faces surrounding him, under a Budweiser-branded chandelier—some white, but almost as many Black and brown, too; more diverse than you’d see in any mainstream wrestling production. “You have the chance to show what you can do. You have the chance to show you belong.”

Black didn’t always lead the locker room speech. Six months ago, after GIPW’s general manager, who was white, unexpectedly died, Black asked the company’s white owners for the opportunity, reasoning that he could connect better with the wrestlers than they could. He’s taken the punches of an indie wrestler trying to make it in the South. He’s hounded bookers to get on a match card and driven hundreds of miles to shows every weekend; he feels the pain of being “stuck on read,” of feeling invisible. And as a Black man, these punches came harder and more frequently.

GIPW’s owners passed the mike. And in Georgia, the second-Blackest of the 50 states, but where

only one Black-owned wrestling promotion exists, this small exchange rings loud, an invitation to say grace at the big, white table of professional wrestling.Out of the 25 athletes on tonight’s card, 11 are Black. An effervescent Black commentator, Tyreke Robinson, will shout into a microphone from a table near the ring. The woman who’ll strike the bell after every three-count pin, Shaloncé Royal, is Black. All five referees, too.

How did a wrestling show on the outskirts of a Georgia city that twice voted for Donald Trump come to be a model of inclusivity? Its bookers set their state’s legacy of segregation aside and hired the best talent.

Early in the 20th century, amateur wrestling promoters gazed out at rows of yawning spectators and decided they’d better find a way to amp it up. So they played God. They fixed the matches and directed opponents on duration, instructing them to exaggerate blows and follow the audience’s cues. Like a comedian bailing on a bad joke, a barrel-chested brawler could suddenly change course if the audience lost interest. Bookers then became writer-directors who weighed stage presence alongside athleticism in the hiring equation. Crucially, they could bring in the talent they wanted, cast wrestlers in roles they created and script how far anyone went.

This remains the rubric for America’s most curious almost-sport. Bookers—from teeny promotions like GIPW to the international juggernaut WWE—pit heels (bad guys) against faces (good guys) in a volley of assault and vengeance so rudimentary that a small child can follow along. Eye rake for an eye rake. Backbreaker for a backbreaker. A match unfolds like a soap opera, the plot thickening with every allegorical strike. It’s a fantastical place where wrestler and spectator enter the fray together and walk away unscathed, invigorated.

“Sports entertainment,” pro wrestling tycoon Vince McMahon calls it, partly as a means of avoiding fees imposed by state sports commissions. And it’s genius, this hyperbolic marriage of storytelling and athletics, where the good guy always comes out on top and the everyman often wears the crown.

Except, not every man has gotten a shot at that crown. Historically, the script, like most in American popular culture, has been written by white people, working off a familiar theme of white supremacy and nationalism. In the early days, promoters cast clean-cut white men, often former college football players or amateur wrestling stars, as faces, while those born outside the U.S.—or whose nationality was perhaps less apparent—were written as heels. Later, promoters employed the American fear du jour to bring the heat, wrestlingspeak for vocal fan disapproval, which in this industry is a good thing. No one could rile up a Cold War crowd like Nikolai Volkoff, The Russian Nightmare, singing the Soviet National Anthem ... except maybe the keffiyeh-wearing Iron Sheik, who culminated his catchphrase, “Iran number one, Russia number one,” by spitting on the ring.

This omission of nonwhite players—and the character tropes doled out to those who have been included—reveals the sport’s truest history, one of white gatekeeping, cultural ignorance and the perpetuation of a white-written script that relies on Black performers as supporters rather than stars. Pro wrestling, a century-old industry, is only now seeing noticeable changes at its highest levels.

Those changes, though, started at the bottom, in bars and barns and strip malls. In elementary school gyms and community rec centers. In places like VFW Post 6605.

Wrestlers tend to remember the match that hooked them, the one they saw as kids that somehow touched them and kept them coming back for more. Black wrestlers might remember when Ron Simmons defeated Vader to become the first Black champion of a major promotion, WCW, in 1992. Or when Kofi Kingston won the WWE Championship at WrestleMania 35, in 2019, making him just the fourth Black man to take that outfit’s heavyweight title. Or they remember the one that got away.

In 2003, a few weeks before Booker T was to face Triple H for the heavyweight title at WrestleMania 19, the two men met in the ring on Monday Night Raw. With the belt draped over his shoulder, Triple H, who is white, stared down Booker T, who is Black, and stated what might as well have been written in the WWE bylaws: “Somebody like you doesn’t get to be a world champion.”

As boos and chants of “A--hole! A--hole!” rose from the crowd, the reigning champ went on. “People like you don’t deserve it,” he thundered while Booker T’s muscled shoulders rose and fell with quick breath. “You’re not here to be a competitor, you’re here to be an entertainer.” Triple H sneered, poked at his opponent’s “nappy” hair and begged, “Go ahead, do a little dance for me, Book. Give me one of those Spinaroonies,” mocking T’s signature breakdance move. “Entertain me. That’s your job.”

When three weeks later a Black wrestler in his athletic prime, beloved by legions of fans of all backgrounds, brought everything he had to the ring and lost, as scripted, to the white heel (who outside of the ring was engaged to McMahon’s daughter), it felt like an awful joke, and it cast an uneasy silence. To the tens of thousands of fans at Safeco Field, and the hundreds of thousands more watching at home—to anyone who understood the arrangement of it all—it shattered an unspoken truth in wrestling: The bad guy can demean, rattle and knock out the good guy, but the good guy always gets his revenge. To another set, though, it was real.

Brandon Whatley was 10 at the time, and he idolized Booker T. “His size, his athleticism, his swagger, his move set. That’s what got me into him,” Whatley says today. “Seeing another Black male on TV, I thought, Hey, that’s kind of cool he can do that stuff.”

In the days leading up to the big event, young Brandon watched a segment about the real-life wrestler, Robert Booker Tio Huffman Jr.—how he’d grown up the youngest of eight kids; how he was parentless at 13; how at 22 he’d robbed a string of Wendy’s and spent almost two years in prison.

“Being Black and growing up in a bad neighborhood, I could relate to that,” says Whatley, who at the time lived in public housing in Anniston, Ala., where his mother used to rush him back to her room, away from the front of their home, whenever gunshots rang outside. “I thought, If he can make it out of that, I can make it out of this.”

Unable to afford the Wrestlemania 19 pay-per-view, young Brandon instead watched clips on recap shows. And the result crushed him. He couldn’t understand how or why someone as undefeatable as Booker T would lose that fight. It was another punch he didn’t deserve.

Fast forward almost two decades—past Whatley’s one year at a for-profit university, then dropping out and waiting tables at a Waffle House, delivering pizzas, transporting car parts; past five years spent wrestling in small-town rings across Georgia and Alabama, training at the Nightmare Factory, a wrestling school owned by AEW’s Cody Rhodes. Now, by day, Whatley works in a warehouse, moving coat hangers; by night, when he’s not training, he earns extra cash making deliveries for DoorDash. But Friday, Saturday and Sunday—those are the days that count, as he clocks hundreds of miles traveling between small-time shows, with one goal. To somehow, someday make a living in wrestling.

“What if [Booker T] had never gotten into wrestling?” asks Whatley, who logged his first match for GIPW last fall. “I don’t know if I’d be a wrestler right now.”

Booker T eventually came out on top three years later, winning the WWE world heavyweight championship—the organization’s highest honor—at The Great American Bash. When it comes to that loss to Triple H, though, he moves past the slight and focuses on the paycheck. “I’ve never … framed my career around any one match,” he said on his podcast in May. “Let alone ... the match where I got paid more money than I got paid for any other match in my life.”

Today WWE has more athletes of color on its roster than ever before, but just being there is not enough. Historically, WWE pushes white wrestlers to the top faster and with more frequency than Black wrestlers. In February, Bobby Lashley, at age 44, became the fifth Black man to hold the company’s highest title, and it came 16 years after he signed his contract. Part of that delay can be attributed to the fact that Lashley left WWE for a decade, starting in 2008, to compete in MMA and wrestle in other promotions—but many people inside the industry link that departure to his butting up against racist forces at the company’s highest rungs. Lashley returned in ’18 and started on a long-coming path upward. (WWE did not offer a comment for this story.)

His, though, is a rare tale. With Black wrestlers in WWE, trajectories have historically been aimed low. And creativity has been curbed. “Their gimmick is typically ‘I’m Black,’ ” says GIPW’s Eric Silva. “That is maybe three things: Either they’re a rapper, a dancer or a criminal.”

History backs up his point. Junkyard Dog wore a collar and chain around his neck. Kamala—actually Mississippi-born James Arthur Harris—wrestled as The Ugandan Giant, who spoke in grunts, wore a loincloth and was escorted to the ring by a white handler wielding a riding crop. In 2007, WWE writers asked Mark Henry to adopt the moniker Silverback, a proposition he publicly and adamantly opposed. A year later, WWE signed Shad Gaspard and Jayson “JTG” Paul, booking them as Cryme Tyme, a duo of fast-talking thugs who greeted the camera with a synchronous “Yo, yo, yo, yo, yo!” Fans got to know them for their pre-show antics: scalping fake tickets, stealing wallets, getting handsy with women and beating people with bats. They spat slang at auctioneer speed, making their words unintelligible to their white opponents, who would say as much before dismissing them.

JTG and Gaspard baked up the characters themselves, as a way in. They knew McMahon would bite, and he did. Asked now if Vince would have cast them as two smart, well-dressed Black men, JTG’s answer is resolute: “No.”

Rather than scripting Black wrestlers as standout stars in singles matches, white writers have typically corralled them into heel stables like the Black Panthers–inspired Nation of Domination, whose militant, anti-white dialogue was written to stoke fear. Recently, a collective branded The New Day—Kingston, Big E and Xavier Woods—has evolved into something promising, but it’s taken a bit of work. In 2014, WWE first introduced the group as choir-backed, dancing preachers.

Increased media coverage of racial inequality has compelled fans of all walks to speak out against WWE’s nasty habits of reserving its most prized belts, largely, for white wrestlers—and of perpetuating offensive stereotypes, like in 2019, when the company sold T-shirts promoting Black wrestler Jordan Myles that evoked racist “Sambo” imagery. Black Writers such as Forbes’s Alfred Konuwa, and The Undefeated’s Martenzie Johnson and David Dennis Jr., are de facto ombudsmen, keeping tabs on the evolving WWE and its sordid moments, including Kingston’s one-sided match against Brock Lesnar in 2019, in which Kingston lost the championship belt in just nine seconds. And WWE’s recent breaking up of The Hurt Business, a crowd-favored stable of wrestlers whose gimmick revolved around them being successful, driven Black men.

Movements like Black Lives Matter and #OscarsSoWhite have inspired structural change, too, if only at the lower levels. In the past two years alone, wrestlers, promoters and fans have banded together to produce all-Black shows, including Black Wrestlers Matter, For the Culture, Good Trouble and the Pan Afrikan World Diaspora Championship. These events have been as much a way for a group of marginalized participants to tell their own stories as they are a response to WWE’s most offensive crime: omission.

But for some small promotions, elevating Black wrestlers has been de rigueur for a while. “Even before me, most of the roster was Black,” says Matt Hankins, proprietor of Georgia's sole Black-owned promotion, Platinum Championship Wrestling (PCW). “When those guys would come down here to PCW,” he says of Black wrestlers who traveled in from other Southern states, “they felt like they’d gone to Wakanda.”

In the indies, wrestlers of all backgrounds create their own characters, bringing amplified or dream versions of themselves to the ring. Unquestionably, there are more Black wrestlers and more Black champions on these lower tiers, because, says Ehren Black, “the big leagues just don’t think we can do it.” And that doubt can trickle down. He remembers sitting on a couch with a friend two years ago, watching WrestleMania 35, when Kingston challenged Daniel Bryan, who is white, for the WWE championship. As Black watched, the apprehension fostered by two decades of fandom crept in. “I thought it was going to be another Booker T situation,” he says. Instead, Kingston pinned Bryan for the win and tears welled up in Black’s eyes. “It was like, Wow, one of us finally made it to the top. I felt like it was a win for all of us.”

Popular culture informs society’s perceptions of people and places. All too often, on-screen messages are color-coded, and in professional wrestling Black has often translated as bad or goofy or unworthy. In a form of entertainment that appeals to kids who often cannot discern fact from fiction, it’s crucial that those wielding power—those who write the stories that shift how people view themselves and others—combat systemic racism by destroying and not perpetuating such stereotypes.

“One of the main reasons we wrestle is because we want people who are younger than us to see somebody who looks like them doing extraordinary things,” says AC Mack, a Black and gay independent wrestler based in Atlanta. “We want them to see people breaking down barriers—hearing no, going around that, and creating their own yes.”

Mack did his part in April, traveling to Tampa to wrestle in two inclusion-themed indie shows—For the Culture and Effy’s Big Gay Brunch—in the days leading up to Wrestlemania 37. But he also saw the long-term rewards of such efforts play out on a larger stage as he attended both nights of WWE’s tentpole event. Watching from 30 rows back, he witnessed nine Black wrestlers compete in singles or tag-team matches (more than at any WrestleMania in history) and four Black wrestlers earn or retain belts (also a record), including the intercontinental championship, which Apollo Crews won over Big E, the first time that two Black men vied for the title at WrestleMania. Throughout, overjoyed fans affixed their tweets with tags like #WrestleMelanin and #BlackestManiaEver.

It’s a start, though, not an end, says Forbes’s Konuwa. “I will be satisfied when it’s like, Of course Bianca Belair is headlining WrestleMania. Of course this Black person won the WWE title. When it’s the rule, as opposed to the exception. You don’t celebrate the country club that finally lets Black people play on the golf course in 2021. It’s embarrassing that the WWE has taken this long.”

Coming from the northeast, the country-road drive toward the military town of Warner Robins crosses through Eatonton, birthplace of two well-known, if disparate, Georgians: The Color Purple author Alice Walker, and Joel Chandler Harris, writer of the Uncle Remus tales. At one point, square in the middle of the state, the path joins with the Antebellum Trail, a 100-mile roadway connecting seven cities that Union general William Tecumseh Sherman deemed too beautiful to burn on his way south in 1864.

In Georgia, this is flyover country. I-75, which connects Michigan’s Upper Peninsula almost to the tip of Florida and slices through the western edge of Warner Robins, is so trafficked by passersby that the Texas-based convenience megastore chain Buc-ee’s built a 53,000-square-foot compound around these parts, with 116 gas pumps that invite travelers to refuel quickly and move on. If you do stop in Warner Robins, it’s likely with aims toward Robins Air Force Base, which is three-quarters the size of Manhattan and employs 23,000 people.

But stick around on a Sunday afternoon and you might discover something else. A few years ago, the directors of the Shia LeBeouf movie The Peanut Butter Falcon, about an aspiring grappler with Down Syndrome, were scouring YouTube for extras working around Savannah, where they were filming. And in their e-combing they found footage of Warner Robins wrestlers pounding it out in GIPW owner Eric Dees’s own backyard. Producers hired the locals, and around the movie’s 1:20 mark Skrilla the Great, who is Black, and Tony James, who is white, bloody each other with fist and chair to tee up the climactic scene.

Dees created GIPW in 2019, starting with that very backyard ring, which he purchased with his National Guard retirement check; it was his way of feeding what he sees as an unsatiated hunger for wrestling in the area. “When WWE comes, the [Macon] Centerplex sells out pretty much every time,” says Dees, who a decade ago was chasing a rap career alongside Skrilla. Now he wrestles as Dee Money and manages the business side of GIPW while Donn Kester, another vet, whose grandfather once ran a wrestling promotion in Kinston, N.C., writes the shows and books the talent.

If WWE is the equivalent of Major League Baseball, and promotions like Ring of Honor, Impact and the newly reborn NWA are the minor leagues, then a hometown show like GIPW amounts to a Saturday afternoon softball league. Which doesn’t make it any less thrilling. Or satisfying. There’s a sense among fans that the creativity in characters and storytelling seen at this level is absent at the higher rungs. “It’s freedom,” says JTG, who after his stint with Cryme Tyme in WWE now wrestles in the indies as Jay tha Gawd. “That’s why I love the independent scene. You’re free to do whatever you want.”

Which is why on a February Sunday night in Warner Robins you’ll see Eric Silva in a grommeted leather getup; and Bryce “Frat Daddy” Cannon in bedazzled blue-velvet hot pants; and Pastor Troy in his clerical collar, escorting Wild Thing to the ring; and Jack Kujo, hanging on the top rope in a jean jacket, pounding his fist to Bon Jovi’s “Livin’ on a Prayer.”

The most effective personas echo their creator’s true self. It’s me, turned up, is a popular line. And so Whatley’s Serpent Assassin is a mashup of his favorite screen heroes: Reptile, from Mortal Kombat; Darth Maul, from Star Wars; Tommy, the green Power Ranger; and Bruce Lee. Silva models his persona after Blade, and the main character on Dexter—“an intellectual bully.” And Austin Towers, The Chief, enters the ring to a song that inspires him, Jidenna’s “Long Live the Chief,” which includes the lyric “You can either sink, swim or be the captain.” (The name, he says, is not meant to evoke any Native American heritage, as was the case with the ’80s-era WWF wrestler Chief Strongbow, who was played by an Italian American.)

A diverse roster brings diverse fans. Tonight, in a community center usually reserved for craft shows and ribeye fundraiser dinners, attendees include a bearded white man wearing a leather vest that announces, beneath an American flag, THESE COLORS DON’T RUN; and a Black father of four, Deundre White, who grew up watching the sport. White points to a kid playing on the floor with a wrestling action figure and reminisces, “I had toys like him. Rings, cages, everything. I was a fanatic, and I am still.”

Between matches, along one wall of the room, wrestlers meet and greet and hold down merch tables. At Whatley’s booth he’s selling a shirt on which his illustrated likeness wields a pair of nunchuks; on another he springs forth wielding a sword. “That’s the ProSouth All-Out Championship,” he says, pointing to a belt displayed next to a grid of 5-by-7 portraits tagged $3 apiece. He earned the belt in December, at an event in Piedmont, Ala. Two weeks before that, he took home the tag-team belt at a Southern Violence and Wrestling show, in Athens, Ga.

At the adjoining booth, Ehren Black hawks short-sleeved EHREN’S GONNA KILL YOU T-shirts and lords over the GIPW tag-team belt that he will defend tonight alongside Towers, his partner in the West Coast Kings. A white kid in neon-green basketball shorts and a fresh haircut walks up to the table. “Ehren?” he asks, as if his hero couldn’t possibly be standing right in front of him.

“What’s up, brother?” Black smiles.

The kid pauses, starstruck. “I’m glad you’re back.”

“Glad to be back.”

The boy looks down, considers his words. “I like when you came back and beat the crap out of Bryce Cannon,” he finally says, recalling GIPW’s December show.

“That was my favorite moment too,” says Black, grinning and laughing.

“He sent you to the hospital. You should’ve sent him to the hospital!” the boy continues, his confidence buoyed by the easy back and forth.

“You know what? That might be the plan tonight,” Black says, beaming a knowing smile. “That might be a good idea.”

An hour later, ring announcer Cliff McDonald booms into his microphone: “The following match is sponsored by the Pat Pawlor, located at 2318 Moody Road, Warner Robins, Ga., for all your pet-grooming needs.” The ensuing match, a tag-team affair between Money, Power, Respect (an all-Black group named after a 1998 hip-hop song that has evolved into a cultural touchstone for Black Gen Y’ers) and a trio called V6 (made up of Latino, Black and white wrestlers), comes to a conclusion when MPR’s Renegade Enforcer, a security guard by day, hits Jack Kujo with a martial-law suplex. Over the course of the next two hours, two in-on-the-act fans will pin Silva to a chair, shouting “One more time!” as Shawn Angelo Montana dispenses kicks to the chin. And in another match, 6' 8" Madman Fulton will put his boot through a drop-ceiling panel when he goes bottom-up in a suplex. (He’ll later apologize to VFW staff and replace the panel.)

The loudest cheers and most guttural boos, though, are reserved for the triple-tag-team championship match between Black’s West Coast Kings, The Menagerie and Exotic Youth, which is governed by GIPW-patented “Unchained” rules: Two men start in the ring, the remaining four are each bound to a post, and the ref frees someone every two minutes. Deep into the contest, with both members of The Menagerie eliminated, Black stands alone in the ring with Cannon, his White Claw-swilling, frat boy nemesis; and Cannon’s tiedye-wearing sidepiece, Cornelious Pepperbottom, both men white and undersized. Pepperbottom hulks a banquet table into the ring, and he and Cannon hoist the wobbling Black toward it. But Black rebounds. He choke-slams Pepperbottom and eyes Cannon. The crowd starts chanting—“Eh-ren’s gon-na kill you! Eh-ren’s gon-na kill you!”—and as Cannon comes at him with a disaster kick Black grabs the incoming leg, thunderbombs Cannon into the table and lands on top of him for the pin.

There’s a pop, ring-speak for an exceptionally loud cheer from the crowd, and Towers leaps in under the bottom rope to join his partner in victory. But while wrestlers and fans alike live for that pop, the most resonant moments can sometimes be much more quiet.

At the start of the third match, a six-year-old boy leapt from his seat and bounced on his haunches as Whatley hopped onto the apron and forward-rolled into the ring, landing in a ninja stance. The child, Deundre White’s son Justin, threw his fists in the air and shrieked as The Serpent Assassin sunk down, burst into a jumping spin-kick and landed in a pounce position. The wrestler jutted his arms out in front of him, one hand closed, one open, forming into the green Power Ranger’s trademark dragon fist, and hissed at the crowd.

To a six-year-old boy, the world shrank down to the size of a 16-by-16 foot ring, and he fixed his gaze upon the man commanding it. Justin jutted his arms out in front of him, one hand closed, one open, forming into a dragon fist. Just like Brandon Whatley.

Alison Miller is a freelance writer and editor based in Athens, Ga.

• NFL Cheerleaders' Fight To Be Heard

• How Michigan Football Failed to Protect One of Its Own From Sexual Assault

• Phillip Adams Took Six Lives, and Then His Own. How Many More Were Ruined?

No comments:

Post a Comment