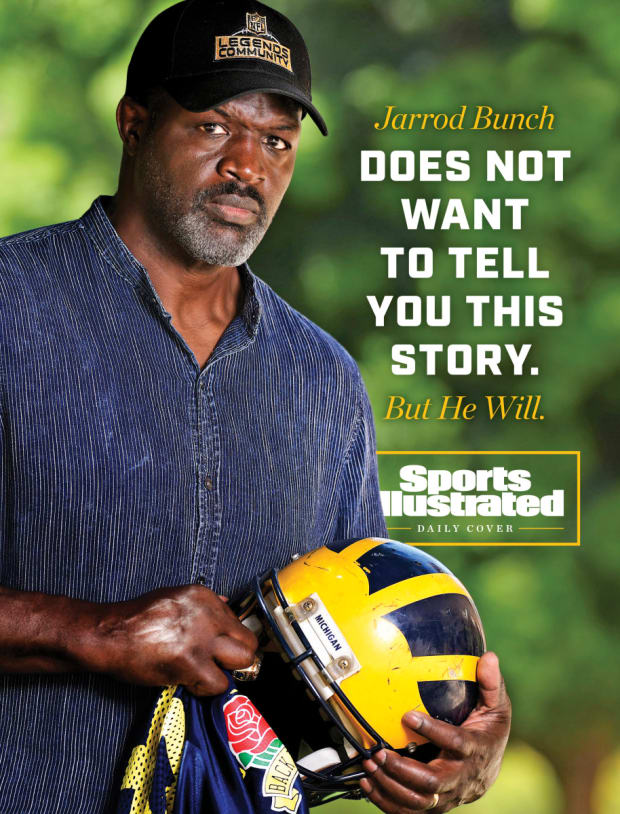

A four-time Big Ten champion and first-round NFL draft pick speaks out about the sexual assault he experienced 30 years ago—and why he never recognized it.

Jarrod Bunch sits down at a restaurant in Playa del Rey, Calif. On his way here, his brother, Milton, called.

What, Milton asked, did Jarrod think of this Michigan scandal?

Jarrod was a football captain for the Wolverines in 1990. He played for five years, at a time when, we now know, team doctor Robert Anderson was routinely molesting players during medical exams.

Jarrod has a story he thinks he should tell, but it’s uncomfortable. He is hoping to share it just once. And so when Milton asked, Jarrod changed the topic. He didn’t want to tell his own brother what he is about to tell you.

Summer, 1986. Bunch is a tailback in Michigan’s top-rated recruiting class—or so he thinks. Coach Bo Schembechler tells him instead, “You’re a fullback.” Bunch doesn’t like it. Tailbacks are stars, scoring touchdowns; fullbacks are secretaries, arranging logistics for tailbacks. He thinks about transferring, but a teammate convinces him to stay.

The Wolverines’ backfield coach tells Bunch that if he moves to fullback, he could start the next year. Bunch tries it, reluctantly, but Schembechler isn’t impressed. He calls the redshirt freshman “soft.” Bunch says now, “It wasn’t that I was soft. I didn’t want to do it.”

Bunch had been a high school star, but that was in his small hometown of Ashtabula, Ohio. Michigan football is another world. The coach is a national celebrity. The helmet is recognized around the globe. More than 100,000 people attend every home game.

Even the medical exams are different. They’re tougher. Players say, “Get ready for your physical” in the same tone they might use for “get ready for wind sprints.” Bunch’s roommate, running back Chris Horn, has already had an exam, and he tried to warn his teammates.

Bunch goes in to see Anderson, the team doctor, in a little office off a training room in a house where Schembechler Hall stands today.

Anderson tells Bunch to drop his drawers. He does a hernia check.

“And then,” Bunch says now, “he’s sticking his finger in your butt.”

Bunch returns to his room in their dorm, South Quad. Decades later, Horn says: “I had never seen a look on anyone’s face like that. It was like he was coming a little bit unglued.”

Bunch is traumatized. But what can he do? He was told to get a physical with the team doctor, so he did. This is 1986. He can’t ask Google about it. He knows about rape—that’s when a man forces himself upon a woman. But the idea that an older male doctor might assault a male college football player is beyond the scope of his previous life experience.

Schembechler has already told Bunch how he feels about him: “I don’t like you. You’re not tough.” Bunch says now, “Those were his exact words. It wasn’t a [psychological] game. If you were not tough, he did not like you. Bo’s thing was: You have to make your body callous. And once your body becomes callous, you can easily withstand any of this. But if you are soft and then you get hit, you can’t make it.”

Bunch is determined to make it. Eventually he becomes a starter, and Schembechler grows to love him. But Bunch is acutely aware of the foundation upon which this new love is built: “I was one of his favorites because I was one of the tough guys. Bo barely talked to me until I started cracking people.”

The entire environment at Michigan is designed to strengthen the weak and silence the grumbling. Players are asked: “Are you hurt, or are you injured?” Injured is an official diagnosis. Hurt is a state of mind.

Throughout, Schembechler tells his players they’d better stay out of the training room—that’s for guys who didn’t train their bodies to get callous. Occasionally, when a player struggles or loafs, somebody will ask: “Are you trying to go see Anderson again, or what?”

Bunch says now, “If you weren't playing hard enough, or if you were missing assignments or whatever, it was that you were trying to get out of it because you wanted to go see Anderson. That was the whole atmosphere. It wasn’t like a whisper. A coach might say it.”

Going to see Anderson means that he will touch body parts he shouldn’t touch and put his fingers in places he shouldn’t put them. And even with the fear that Schembechler might think they were soft, players had to go see Anderson frequently, because they broke bones and pulled muscles and, as they said back then, got their bell rung. Horn remembers: “I woke up one time in Dr. Anderson’s office butt-naked, after a concussion.”

It is fair to wonder now how such widespread abuse could go unreported. But Bunch makes the point that it was so widespread that it was hard to recognize it as abuse. “Everybody was going through the same thing, so everybody knew what was going to happen. You knew, like, I never had that before—but everybody else is getting the same thing.’ ”

Bunch does not mean that literally everybody went through the same thing. His teammates can tell their own stories. But Anderson assaulted so many of them that it normalized his behavior.

During Bunch’s five years in Ann Arbor, Anderson keeps assaulting the running back at exams. He asks Bunch about his girlfriend. Gropes his genitals. It all registers enough that Bunch will remember it in detail years later, but as a college student in the 1980s he can’t fully understand how wrong it is. The psychological effect is akin to that on a child in a dysfunctional home who doesn’t know what a functional home is like. Bunch has never played for another college football program. He does not have the benefit of context.

At one point he sees another doctor at Michigan—one unaffiliated with the football program. That exam is very different. Less invasive. Bunch even tells that doctor what Anderson has done, and the doctor says, “That’s not right.” But Bunch still does not understand that Anderson has been violating him. He just figures that football exams are more rigorous than others.

One night in the offseason he’s hanging out with friends at a pool when a dog darts in front of him. He jumps out of the way and falls. The next morning, he wakes up to find blood on his sheets. It’s coming out of his penis. He goes to see Anderson.

“He was testing, like, to see if my penis was broken or something,” Bunch says now. “I told him, ‘I didn’t [get hit there].’ He touched my balls and he's like, ‘I think you just bruised something.’ ”

Bunch says the doctor seemed more interested in touching him than in where the blood was originating: “He didn't give me a test. He didn't give me an X-ray.”

Even after this, Bunch still does not consider complaining to his coaches. “You did not want to have a bad report from Anderson, or any doctor,” he says now. “If [the doctor says], ‘Bo, he's not doing this or doing that,’ it could mess the whole thing up. I did not want to be in trouble.”

Besides, Bunch’s conclusion from all of these experiences is not that Anderson is some serial abuser of patients. It is that Anderson is part of a larger apparatus that expects players to subjugate their own interests in favor of the team.

Schembechler says it all the time: The team. The team. The team. Robert Anderson does not work for Jarrod Bunch. He works for the team. Bunch leaves Michigan in 1991. He does not realize it but, in a way, he takes Anderson with him.

Summer, 1991. The Giants just drafted Bunch with the 27th pick. He has already won four Big Ten titles, so he is ready for the NFL and all that it entails: stronger players, bigger collisions … and medical exams at least as rigorous as the ones he had at Michigan.

He goes in for his physical. He walks out surprised.

“I’m like, ‘Oh. That’s it?’ ” Bunch says now. “I did not understand the difference until I got to the pros.”

He now has two pieces of information: Anderson’s exams, and the exams by the Giants’ team doctors. As a detached observer, one might expect him at this point to realize that what happened in Ann Arbor was terribly wrong. But Bunch is not a detached observer. He is damaged, and he doesn’t even know it.

“I saw all doctors as They’re not working for me,” Bunch says, “because of how Anderson did it. My perception of doctors came from Anderson.”

Here he hits the table for emphasis. This point is everything. A boy with abusive parents might see all authority figures as untrustworthy, no matter how nice and well-meaning they are. This is how Bunch saw all doctors.

In his second NFL season Bunch runs for 501 yards, at 4.8 per carry—outstanding numbers for a fullback. Jarrod (pronounced like Jared, though announcers routinely say Jur-ODD) is named the Giants’ Offensive Player of the Year. But before his third season, during training camp, he gets hit in the right knee.

Thankfully, his body is callous. He toughs it out and plays 13 regular-season games, starting eight, with a torn MCL and torn retinaculum. When the season ends, team doctors tell Bunch that he has two surgical options: realignment, which will keep him out for the next year; or a lateral-release procedure, which will allow him to come back sooner. They recommend the lateral release, but Bunch does not trust them. He thinks they just want him back on the field quicker.

He goes for a second opinion, which is the same as the first: Realignment will keep him off the field longer and carries some risk. The Giants’ doctors were right. But Bunch doesn’t care. They’re not his doctors. They work for the team. He finds another doctor to perform the surgery.

Now the Giants don’t trust him. The relationship between player and team is fractured. In 1994 he holds out from training camp, saying he wants to be fully healthy before he signs. The New York Times calls it “one of the strangest holdouts the team has seen.” The Giants send him a letter: He has five days to show up. Instead he ends up on the physically unable to perform list, gets cut at the end of camp, signs with the Raiders, plays three games, lacks his former explosiveness … and soon his career is over. The NFL moves on that quickly.

In the ensuing years, for a period of time so long that he can’t even remember when it started, Bunch feels pressure above his groin. But he refuses to tell doctors. He doesn’t want another hernia exam, like the ones Anderson used to give him. When doctors ask him whether he feels any discomfort, he says he’s fine. Finally, in 2015, he coughs and feels serious pain. He realizes he has to tell a doctor.

“I think I got a hernia,” he says.

He undergoes surgery, and actually he has two hernias. So in 2017 he has another surgery. And in ’19 a third. He will wonder, someday, if he needed so many procedures because he waited so long. It’s a big question, but not the biggest one.

Summer, 2021.

The Michigan scandal has exploded and Bunch tells his wife, Robin, about the “physicals” that Anderson gave him. Robin understands immediately what Jarrod could not understand for years. He turned 18 in the summer of 1986. He was healthy. He did not need a real prostate exam, let alone what Anderson said was a prostate exam. Robin tells her husband that Anderson wasn’t supposed to be doing what he did.

“And I'm like, ‘I didn't know,’ ” Jarrod says now. “She's like, ‘How could you not know?’ ”

What makes him really mad is that Michigan did know. It’s in a report that the school commissioned and released this May. In 1975, a Michigan wrestler named Tad Deluca complained in writing to his coach, Bill Johannesen, that “[something] is wrong with Dr. Anderson. Regardless of what you were there for, he asks that you ‘drop your drawers’ and cough.” In ’79, two psychological counselors at Michigan reported concerns to Thomas Easthope, the school’s assistant vice president of student services.

Anderson resigned as the head of University Health Services but kept his job as director of athletic medicine. Easthope approved a salary increase. In 1980, there was another complaint against Anderson. Soon after, Anderson began working full-time for the athletic department, where he was ready to ambush a kid from Ashtabula, Ohio.

“This guy was [reassigned] for this,” Bunch says. “And he was sent to the athletic department to work with football players. That’s what really pisses me off.”

Now Bunch sees what happened all too clearly. He read that Anderson allegedly gave students medical exemptions to avoid the Vietnam War draft, and he thinks now that Anderson asked about his girlfriend all those years ago as a way to test how far he could go with Jarrod, whether he was receptive to being with a man. “That is when I’m like, ‘Ugh.’ He was trying to figure [it] out.”

Michigan’s board of regents released a statement in March saying, in part, “We are sorry for the pain caused by the failures of our beloved University.” But the school has not settled the case. And Bunch doesn’t know what to think. All these years, he believed he had a good relationship with the university, that it was proud of him and saw him as one of its own.

“It's clouding my judgment,” he says. “Instead of like, Look, we know this was wrong, let’s finish it, get this done, so everybody can be whole and we can start repairing our relationship, they’re fighting the s---.” (A Michigan spokesperson says the school is “actively engaged in a confidential, court-guided mediation process with the survivors of Dr. Anderson's abuse.”)

This, he says, is why he is sharing his story. He says, “The truth is the truth.” Bunch did not want to have this conversation with his brother. Horn has not told some of his own family members. Neither man enjoys sharing this truth, but Bunch thinks it is important to do it at least once because he owes it to other players who spoke up recently, like little-remembered Gilvanni Johnson or Daniel Kwiatkowski. It is easy for some to dismiss Johnson and Kwiatkowski as bitter because they didn’t achieve college stardom. But what do you say about Jarrod Bunch?

“Four Big Ten championships, man,” he says. “Captain of the football team. Drafted in the first round. Was it the best? No. But what’s my complaint?”

Bunch saw Schembechler intermittently between 1991, when Bunch left Michigan, and 2006, when the coach died. He says, “Away from [football], he was a great guy. But he didn't want anything that's gonna mess up his program.” That program has long been promoted as different, special, on higher moral ground than other big-time programs. Schembechler preached as much. Now Bunch wonders whether this created the very environment that allowed Anderson to thrive: People in the Michigan football program were so sure of its superiority that nobody was willing to question it.

Bunch goes off on a rant about his alma mater … and then he asks that it not be put in the story. He’s worried that he sounds like he hates Michigan—that his words might even be used against the school in recruiting.

Jarrod Bunch doesn’t want to hate Michigan. He wants to love Michigan again. But he wants to know that the school loves him, too.

• For Ohtani, and Others, an Interpreter Is So Much More Than You Think

• Phillip Adams Took Six Lives, and Then His Own. How Many More Were Ruined?

• Tragedy and Hope: A Prospect, a Scout and a Pop Fly

No comments:

Post a Comment